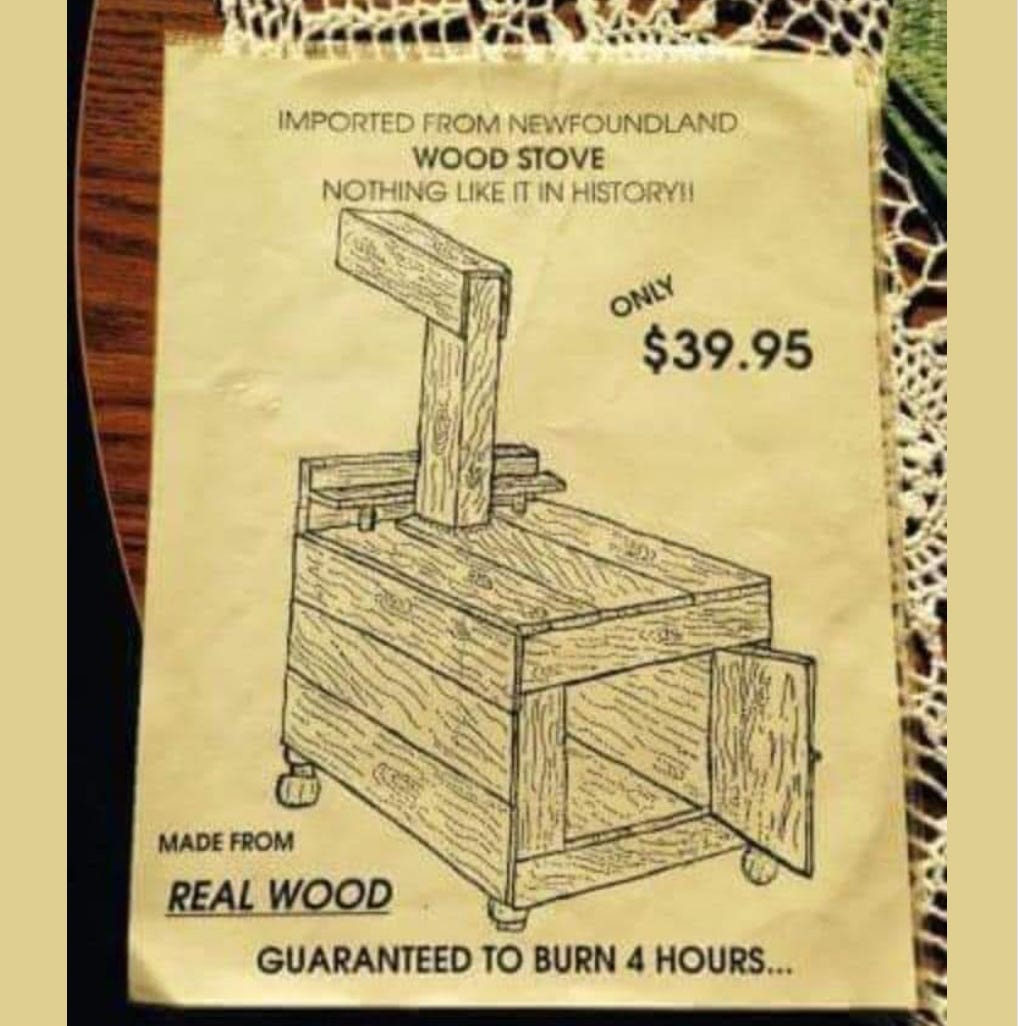

Sunday Strip: Just say No

and watch out for reindeers!

| DR. ROBERT W. MALONE NOV 30 |

Public health alert!

A different take on an old classic!

Don’t think it couldn’t happen to you!

Malone News is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Thanks for reading Malone News! This post is public so feel free to share it.

Ending today’s Substack with a true story.

Just say… NO

She just said…”no”

Dr. Frances Oldham Kelsey was born on Vancouver Island in 1914, in a small fishing village called Cobble Hill. Her childhood was not one of privilege, but it is said that she threw herself into reading, with a curiosity that could not be contained.

Kelsey won admission to McGill University, where she studied pharmacology. She graduated with honors and was quickly recognized by leading researchers for her meticulous attention to detail.

In the 1930s, discrimination was so baked into academia that when McGill professor E.M.K. Geiling requested a new graduate assistant, the university, assuming “Frances” was a man, sent her name. He was surprised when she arrived, but her work ethic won him over. With Geiling she helped investigate a series of tragic deaths linked to a toxic solvent in a sulfanilamide drug formulation, an early experience that shaped her lifelong insistence on drug safety.

She earned her Ph.D. in 1938 at the University of Chicago, and then a a degree in medicine in 1950, making her a dual-trained physician-pharmacologist.

The Call From Washington

In 1960, at age 45, Kelsey applied for a medical officer position at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. The FDA also assumed that “Frances” was a man. But they quickly learned that she was, as one coworker later said, “the toughest reviewer in the place.”

Her very first major assignment seemed routine. She was to review a new sedative widely marketed in Europe for anti-nausea in pregnancy. The drug was called thalidomide, and the review was considered a formality for approval in the United States.

The Woman Who Said No

Kelsey refused to sign off.

She noticed details that others ignored:

- The company had not provided rigorous U.S. clinical trial data.

- Peripheral neuropathy was showing up in European patients.

- Animal studies were incomplete.

- Most importantly, no one had tested it for effects on pregnancy, despite its heavy use by pregnant women.

By regulation, she could defer approval for thirty days. So as each month rolled around, she put in another deferral. For a new employee, this was a radical thing to do.

For months, the drug company pressured her: phone calls, letters, meetings, repeated complaints to her supervisors. But Kelsey held firm. She had seen what rushed approvals could do. Something about thalidomide felt wrong.

Then, in late 1961, what she feared became a reality: reports poured in from Europe and Australia of babies born with catastrophic limb deformities, a condition called phocomelia, after their mothers took thalidomide early in pregnancy.

National Recognition Came Swiftly

In 1962 President John F. Kennedy awarded her the President’s Award for Distinguished Federal Civilian Service, one of the highest honors a civilian can receive. Kennedy praised her refusal to bow to commercial pressure and noted that her actions had saved countless families from heartbreak.

Her work also triggered the passage of the 1962 Kefauver-Harris Amendments, which transformed the FDA and made modern drug regulation possible: requiring proof of safety and efficacy, informed consent in clinical trials, and strict oversight of advertising claims.

Unfortunately, this act was diluted by the 1997 FDA Modernization Act (FDAMA) which paved the way for modern advertising, by allowing more direct-to-consumer (DTC) broadcast ads.

A Lifelong Career in Drug Safety

Kelsey continued her work at the FDA for many decades. She led the new drug evaluation office, mentored younger scientists, and remained a fierce advocate for evidence-based medicine.

Even in her 80s, she was still teaching and reviewing cases. At age 90, she retired.

Frances Kelsey lived to be 101. She died in 2015, just two weeks after the Canadian government formally recognized her as a national hero. It only took the Canadian government 55 years to recognize her accomplishments. During her long career, she never received the Nobel Prize in Medicine, as that is reserved for discovering something new, rather than preventing harm.

She never sought fame. She never cashed in her story. She remained, throughout her life, a scientist committed to one principle: patients deserve protection, not assumptions. That informed consent is paramount for patient’s right.

So, remember to stand up and defend what is right – even in the face of tyranny. And never forget that famous Thomas Jefferson quote: