1947 – 33 Trappist Monks

August 1947 – April 1948 Yangjiaping, Hebei asiaharvest.org/china

The Cistercians are one of the many branches of the Catholic Church. Also known as ‘Trappists’, they were founded in 1098 when a saintly abbot named Robert led 21 monks to a remote location of Citeaux, France, where they followed Benedict of Nursia’s ‘Rules for Monasteries,’ written in the sixth century. Trappist monks are characterised by the vow of silence, which applies whenever they are on monastery grounds. From time to time the monks are expected to leave the monastery and share the spiritual lessons they have learned with people in the outside world.

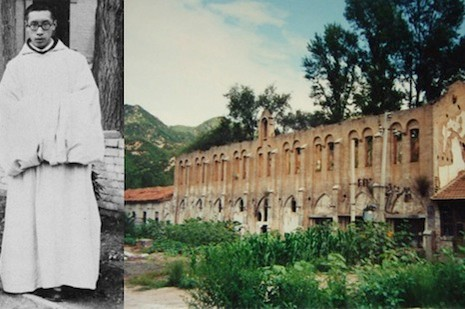

In 1883 a Trappist monastery was established in the mountains of north China at Yangjiaping, just outside the Great Wall, about 80 miles (130 km) north of Beijing. Through great ingenuity and much sweat and tears they carved the monastery grounds out of 10 sq. miles (26 sq. km) of completely barren land, gradually transforming it into a useable condition. One report sayid:

“In the Trappist tradition, the area chosen by the monks…was remote and difficult to reach. Indeed, Yangjiaping was sufficiently isolated that a journey of three days by mule was required to reach the abbey from the nearest railway stop. When the Trappists first came to their hundred square-mile foundation it was virgin wilderness, and the early monks frequently encountered tigers and leopards.”[1]

The monks’ aims were the perusal of quiet meditation, peaceful contemplation, agricultural cultivation, and social work. Although European missionaries had founded the monastery, by the time of the Communist persecution, only a handful of the 75 monks residing at Yangjiaping were foreigners. Over time these harmless men won the respect of the local community to such an extent that people would not cut wood from the forests around the monastic lands. Ironically, the remote location chosen for the Yangjiaping Monastery also turned out to be a strategic location for military manoeuvres during the chaotic 1930s and 1940s in China.

During the Second World War, Japanese troops entered the monastery and stole the monks’ grain and other food. When the Communists came into the area they decided the monks had willingly helped the Japanese by providing food for them. The Communists hatred for the Catholics was obvious. Whenever Japanese troops drew near,

“Communist guerrillas fired off guns whose fire seemed to come from the monastery itself. Their agents painted abusive anti-Japanese slogans upon the monastery walls. These things brought down on the monks reprisals from the Japanese—as they were intended to do.”[2]

In the summer of 1947, a sequence of events that led to the end of the Yangjiaping monastery began. On July 1st two lay brothers herded goats and cows near the monastery were arrested and sentenced as “oppressors of the people.” A large mob consisting of more than 1,000 people from 30 villages were summoned to a mock trial at the ‘Peoples’ Court’, where all kinds of imaginary crimes were shouted at the startled monks. The furniture and other belongings of the monastery were given to people who accused the monks of various imagined crimes at staged public rallies, including some “witnesses” who were trucked in from faraway locations.

The monks had never seen any of these ‘professional accusers’ before. One man was awarded the rectory furniture because he reported his parents had been “frightened” by foreigners in 1909! The monastery’s cows and goats were confiscated and given to locals, while ten tons of grain and other supplies used to feed the poor were stolen to feed Communist troops. Just a few years previously the grateful local community had presented a memorial tablet to the monks, saying “The benefits you have brought us are as weighty as the mountains.”

The mob completely stripped the buildings bare of any removable item. Even the leather covers were torn from books in the monastery library, while the invaluable volumes were discarded on the floor by the illiterate peasants. The Communists took away the eye-glasses used by most of the monks, arguing that the villagers didn’t wear glasses, so why should they? It was later learned that some local Catholics had surreptitiously joined the looters in order to safeguard the sacred vessels and vestments. During the looting,

“the monks knelt in silent prayer for their oppressors. One by one the Trappists were called into the church to stand trial before the altar, where commissars stood armed with clubs to beat them into ‘confessing’. A Catholic woman who protested—her name was Maria Chang—was beaten into unconsciousness and dragged from the church.”[3]

Maria Chang had shown remarkable courage and boldness. She told the judges the truth—that the monks had only come to China only to share Christ and to help the poor. The beating she received was so severe that many thought she had died. Guards threw the church banner over her body. Maria recovered, but was placed under arrest and held at Yangjiaping for months. The judges were embarrassed by Maria’s courage, and determined not to let any other people make speeches to prevent a similar occurrence. The judges moved straight to the ‘peoples’ verdicts,’ calling out names of monks and asking the mob for their decision. One by one the people shouted, “Death!” By the end of the farcical proceedings, the result was

“condemnation to death of a number of the monks. They were accused of conniving with the Japanese in the first instance, and then of collaborating with the Nationalist Government. The other monks were at first sentenced to prison…. They were ordered to leave the monastery. They were forced to leave with their hands tied behind their backs.”[4]

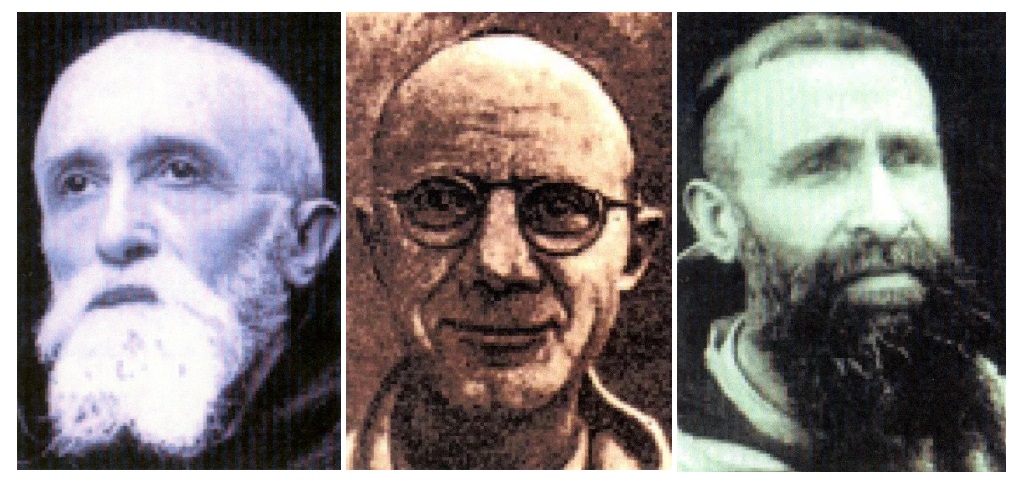

After the looting was over the French abbot was shackled to the frozen ground for two months as punishment. He and two other French priests were later expelled from China.

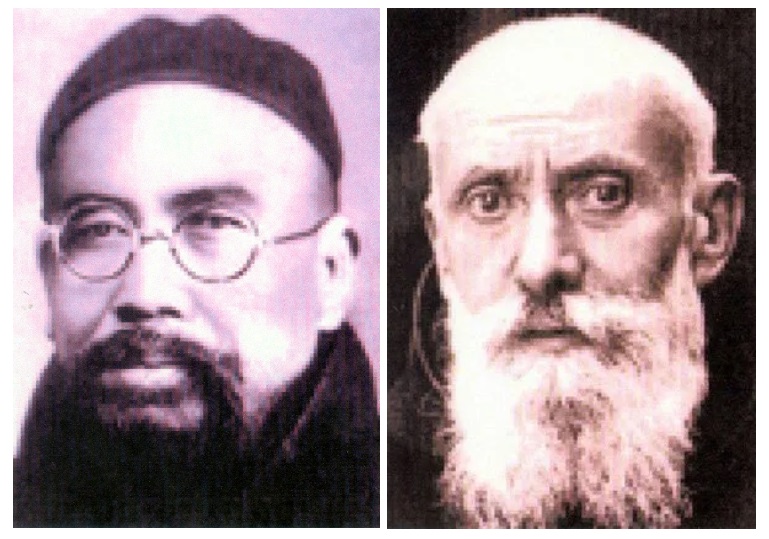

Most of the Trappist martyrs died during an exhausting death march of approximately 100 miles (162 km). On the evening of August 12, the Communist commander, Li Cuishi, decided to use the monks as pack-animals to move supplies from the monastery to an army battalion at Zhang Gezhuang. The monks were forced to march over extreme terrain day and night. The freezing winter wind cut their bodies. After returning to the monastery three men, including 82-year-old priest Bruno Fu, died on August 15, 1947, from the sheer physical exhaustion and mental strain of their ordeal. Fou had been due to celebrate 50 years as a priest on the very day he died. The celebrations would certainly have exceeded all his expectations as he was welcomed to heaven by Jesus whom he had loved and served for so many years.

The men who survived soon came to envy those who had died. They were “handcuffed with wire tightly bound around their wrists. It was to stay there for weeks and months, so that when they ate, they were forced to lap up the food from the ground, like animals.”[5] Clement Gao, aged 75, dropped dead from exhaustion as he returned to Yangjiaping on August 18th, while Philip Wang Liu, also in his 70s, fell in the doorway after reaching his beloved monastery and never recovered. For those who had survived the initial ordeal, only a short recuperation was allowed before they were ordered to do another march on the night of August 28th. Along the way they were made to sleep in pig-pens. To entertain their captors, daily ‘trials’ were held, where the ‘accused’ were beaten for the soldiers’ sadistic pleasure. This death march took place

“in beating rain and violent winds, across steep, rugged mountains. The younger monks tried to help or even carry the older ones. All had to survive on meagre rations of dry cereal. Guards, enduring in part the same miserable hardships, vented their anger and frustration on the monks. There was no mercy.”[6]

On the night of September 6th, as the group approached Ma Lai village, one of the younger monks carrying the 69-year-old Frenchman William Augustin Camborieu stumbled and fell on the mountain trail. The frail priest’s head was cut open on a jagged rock and he bled to death. Camborieu had already endured imprisonment at the hands of the Japanese a few years earlier. After his release he could have easily returned to the comfort of his native France, but he chose to remain in Yangjiaping because of his love for China and his desire to serve God.

When the march reached the village of Dengjiayou, Trappist priest Albert L’Heureux[7] felt that he had reached the end of his life. The Canadian-born priest signalled this to the other prisoners with the sign-language Trappists use to communicate with each other during the times they observe a vow of silence. L’Heureux was a former Jesuit theologian who had received permission to leave his former order and dedicate the remainder of his life to monastic prayer and meditation, and so transferred from Hangzhou in Zhejiang Province to the Trappist Monastery at Yangjiaping.

L’Heureux’s hands had been “bound together behind his back with steel wire for more than one month when he arrived at Dengjiayou. His wrists had swollen, and the bones were visible in the horrible wounds.”[8] That night the Canadian passed away. His body had simply expired from the toll of inhumane torture and stress. The next morning a young soldier told the survivors,

“‘He died very peacefully. He looks like that man on the figure-ten frame in your church.’ In Chinese the figure ten is a cross. Brother Marcellus and the three others who went over to bury him had to agree. They found [his] legs crossed, the shrunken right foot resting above the left. The swollen wrists were resting on his breast. There was something deeply beautiful about his emaciated face. Christ had died again for China in his beloved monk.”[9]

Perhaps one indication of the horrors endured by the Trappists can be seen in the fact that the survivors did not give any detailed account of the events for more than 30 years. L’Heureux’s colleague, Father Sebastian, later wrote:

“We took him out and laid him on a stretcher. He did not look like a corpse at all, smiling as he was, with both hands crossed over his breast. Bending on one knee, we took up the stretcher and as we walked, we looked at his smiling face and we prayed for him. When we reached the slope of the mountain, we dug a hole only about one foot deep and buried him, because it was raining and the soldiers would not wait.”[10]

The gentle monks were forced to endure a terrible 25-day stay in Dengjiayou village, during which

“The whole charade of the Peoples’ Court began again. The brutality was worse than ever. And meted out on bodies already severely debilitated by all the hardships of the death march. And the goal of the persecutors? It was now nothing less than that these monks would deny the very existence of God. For the Communists were establishing an atheistic state that would be purged of the opium of religion.”[11]

Because of the incredibly filthy conditions, the stay at Dengjiayou achieved nothing but to further break down the physical and mental health of the prisoners. One report says,

“All lived in conditions of incredible filth, and those who had their hands unbound tried to help their shackled and bound brothers remove lice and other vermin from their unwashed bodies. It was later reported that several of the monks whose hands were bound had almost literally been eaten to death by the vermin which afflicted them.”[12]

One priest, Maurus Bougon, tried to escape from the Communists during the death march. They soon recaptured him and cut off both his feet as punishment, and later executed him to put him out of his misery. A 60-year-old French priest, Stephen Maury, had invested many years of his life in China. Unable to bear the load of the death march, he was carried into Dengjiayou by four of his brethren on September 8th. As soon as they entered the village, Maury breathed his last and passed into the presence of God. Two days later, on September 10, Marcus Li Chang, a 62-year-old monk from Hejian in Hebei Province, also surrendered his life as a result of the intense strain.

During one agonizing day (September 15th), three more Chinese Trappists died. Their names were Matthias Ying[13] (a native of Shandong Province), Aloysius Ma,[14] and Andreas Li. Five days later Bartholomew Qin (aged 54), and Aloysius Ren[15] (75) also perished. Their bodies were placed in shallow graves and dug up by hungry dogs and wolves which ate the flesh and left body parts strewn about the village. To the Trappists, funeral rituals are extremely elaborate, and death is considered a monumental event to be cherished and honoured. To have limbs and body parts of their beloved colleagues devoured by beasts was almost too much for the survivors to bear. More sorrow was added to the monks when they were told the Yangjiaping Monastery had been destroyed. Three of the believers were allowed to return to see for themselves. The huge stone walls remained standing, but everything inside the monastery had been reduced to rubble.

The 62-year-old Prior of Yangjiaping, Anthony Fan, suddenly died on October 13th. The final French priest to die was the acting superior of the community, the 70-year-old Augustine Faure, who perished on October 18th. The fact that these two men’s health had appeared to be improving led the others to suspect they were poisoned.

Even after some of the prisoners were released the impact of the brutal summer continued to reap a harvest of martyrs. On October 31, the 66-year-old Lucas Fan died at Zhejiadai in Hebei Province, as did Malachi Chao and Amadeus Liu on November 1st. In late November and throughout the month of December heaven’s scroll of martyrs was added to by the names of Franciscus Shu (aged 48), Henry Chang (50), Thomas Zhao (45), Michael Xiu (46), Simon Shu (50), and the aged Gabriel Dian (86). Aelred Drost (37), from the Dutch abbey of Tilburg, went to his ultimate reward on December 5th.

On January 18, 1948, Basil Geng (32) died at Huanghuagou. The Communists believed Seraphim Shu (38) was the future leader of the monastery, so he was tried and beaten more than 20 times. By the end, “his thumbs were wired together behind his back, his big toes were wired together, and then a short wire joined the two links. He could only kneel or lie on his side.”[16]

February 5th “was a particularly fateful day. After suffering so much, Seraphim and the 29-year-old Chrysostom Zhang were taken out and laid on a flat stone. Then their heads were crushed with sharp stones, and they were beheaded. At the same time four brothers were shot: Brothers Alexis Liu, Damian Hang,[17] Eligius Sui[18] and John Miu.”[19] Damian Hang had excruciatingly had his hands wired behind his back since July 23rd the previous year, and his feet had been crippled from an earlier frostbite. In the end, “he could only crawl about. And for this he was confined and subjected to additional abuse.”[20] Information was later received that

“six of the Brothers had been beaten to death with clubs. Still later, five of the Trappists and a lay catechist from Banbu were all stoned to death—a death which, in China, means laying one’s head upon a heavy stone, while another is dropped to smash the skull. Brother Wang died of blood poisoning from the festering wounds on his bound wrist. Two more of the monks died in jail in 1951. In all, 33 of the 75 Trappists perished from the death march punishment.”[21]

The final recorded Trappist death resulting from this barbarous persecution was that of 32-year-old Thomas Yuen who died at Mujiazhuang, Hubei, in April 1948. It is likely that the true number of Trappist monks who died from the tortures of 1947 and afterwards is higher than those martyrs named here. Many of the Chinese believers who were released into society and never heard of again. The monks who survived the carnage realized the New China was no place for their ministry. In addition to their physical ailments, they suffered major psychological scars which most of them carried to their graves. A small group of survivors was led to the safe environment of Hong Kong by Paulinius Lee, who founded the Trappist Monastery on Lantau Island which continues to function to this day. Because of the humble nature of the Trappist monks and their refusal to seek any publicity, this terrible incident has rarely been mentioned in the annals of Chinese Church history, even though it ranks among the worst atrocities ever committed against any group of Christians.

© This article is an extract from Paul Hattaway’s epic 656-page China’s Book of Martyrs, which profiles more than 1,000 Christian martyrs in China since AD 845, accompanied by over 500 photos. You can order this or many other China books and e-books here.

1. Myers, Enemies Without Guns, 1.

2. Palmer, God’s Underground in Asia, 8.

3. Palmer, God’s Underground in Asia, 28.

4. Galter, The Red Book of the Persecuted Church, 170 (f.n.10).

5. Palmer, God’s Underground in Asia, 28.

6. Taken from “China’s Hope: The Story of the Chinese Cistercian Martyrs 1942-1949,” published on a website which is no longer operational.

7. Some accounts give his first name as Alphonso.

8. Myers, Enemies Without Guns, 11.

9. “China’s Hope: The Story of the Chinese Cistercian Martyrs 1942-1949.”

10. Patrick J. Scanlan, Stars in the Sky (Hong Kong: Trappist Publications, 1984), 295. Other eyewitness accounts of the terrible massacre of Yangjiaping are Stanislaus M. Jen, The History of Our Lady of Consolation, Yang Jia Ping (Hong Kong: n.p., 1978); Stanislaus M. Jen, The History of Our Lady of Joy (Liesse) Written for Its Golden Jubilee of Foundation (Hong Kong: Catholic Truth Society, 1978); and Jeroom Heyndrickx (ed.), Historiography of the Chinese Catholic Church: Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries (Louvain Chinese Studies I, Leuven: Ferdinand Verbiest Foundation, 1994).

11. “China’s Hope: The Story of the Chinese Cistercian Martyrs 1942-1949.”

12. Myers, Enemies Without Guns, 11.

13. Some sources give Ying’s first name as Emile.

14. Some sources give Ma’s first name as Conrad.

15. Some sources give Ren’s first name as Gonzaga.

16. “China’s Hope: The Story of the Chinese Cistercian Martyrs 1942-1949.”

17. Some sources give his name as Damien Wang.

18. Some sources give his name as Elgius Zi.

19. “China’s Hope: The Story of the Chinese Cistercian Martyrs 1942-1949.”

20. “China’s Hope: The Story of the Chinese Cistercian Martyrs 1942-1949.”

21. Palmer, God’s Underground in Asia, 29.

==============================

mail: